American researcher Yarelix Estrada was the first woman to publicly denounce Julián Quintero, director of the Corporación Acción Técnica Social (ATS), for alleged harassment and sexual abuse. Volcánicas interviewed Yarelix and two other women, whose identities will be protected, who also affirm that they were victims of Quintero’s abusive behavior. All three share their testimony in this report.

These testimonies were submitted by the legal organization representing the victims — attorneys Susan Espitia, Juliana Higuera, and Laura Páez — and verified by Volcánicas through direct interviews and supporting documents. The names of two of the victims have been changed at their request to respect their privacy and prevent reprisals, and their identities, as well as the aforementioned documents, are protected by the constitutional guarantee of journalistic source protection (Article 74 of the Colombian Constitution).

Yarelix Estrada

Yarelix Estrada, a researcher and harm reduction activist affiliated with the New York City Department of Health and with drug checking initiatives in the United States and other countries, was the first to publicly denounce Julián Quintero. According to her testimony, the acts of harassment and sexual abuse occurred on two occasions: in Vienna in March 2025, and in Bogotá in July 2025, after she decided to move to the city, motivated by her work and by the friendships and trust she had built with Quintero and others from Échele Cabeza. Estrada was 31 years old, and Quintero was 47.

Vienna, March 2025.

Yarelix recalls that during a United Nations drug policy event in Vienna in March of this year, she and Quintero shared accommodations with other people from the harm reduction sector. Estrada maintains that after a night of drinking alcohol, Quintero undressed her and sexually assaulted her while she was very intoxicated.

“In March 2025, I spoke at the United Nations in Vienna. It was my second time speaking at the UN, and I stayed with the ATS and Instituto RIA group. A large group of us stayed together in a large shared apartment and divided up the rooms to save money. Julián Quintero was one of the people who stayed in that apartment. On the night of March 12, we all went out to a party; I drank a lot, and when we returned to the Airbnb, I was really drunk. We may have continued drinking once we got there. In that state, I remember Julián starting to hug me; then he grabbed me and took me to another room, separate from where everyone else was. As we walked, I remember asking him, confused, ‘Weren’t you in a relationship?’ Once in the room, he started taking off my clothes (I think I was wearing a dress) and also took off my bra. He started touching me. I don’t remember how far things went because when I started to regain consciousness, I realized what was happening, and I decided to pretend to fall asleep. I didn’t like what was happening. I didn’t want to be with him, but I was aware of the power dynamic at play with someone who is a leader in harm reduction in the country I was moving to in a few months. I was also struggling with the discomfort of having to tell a friend to stop while I was in that state. The easiest reaction I could think of was to pretend to fall asleep so he would leave, and that’s what happened.

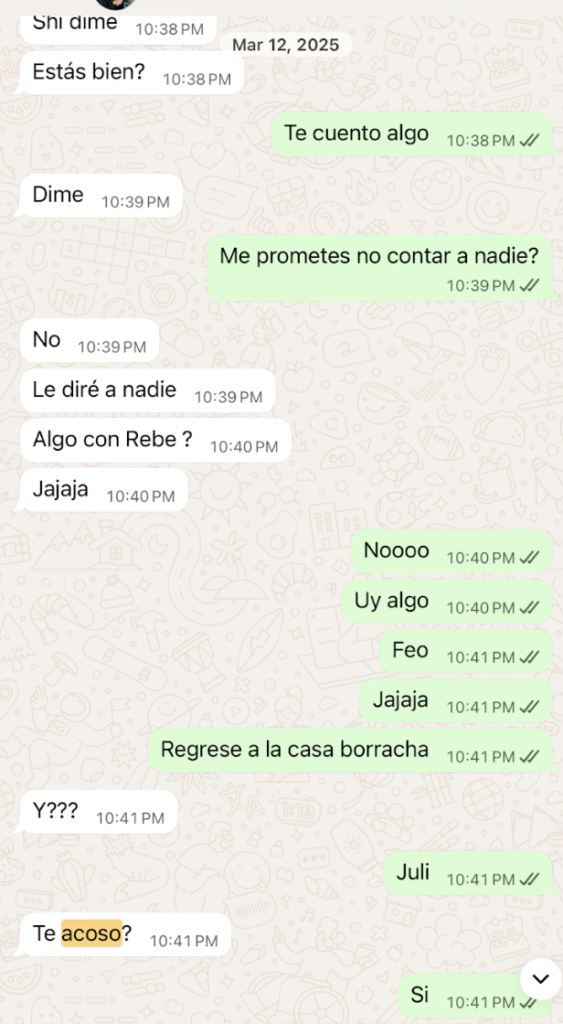

That same night, I texted a friend telling him what had happened: that I hadn’t felt comfortable, that I hadn’t wanted it. It felt like I’d been assaulted, but at that moment I didn’t know what words to use. It was all too complicated. So I decided not to say anything else after that”.

Bogotá, July 2025.

Months later, Estrada moved to Bogotá. After going out to eat with Quintero, she went to the Échele Cabeza headquarters in the Teusaquillo neighborhood, where she continued an informal gathering with colleagues during which alcohol was consumed. Estrada recounts that she fell asleep and woke up in another room, at the back of the Échele Cabeza house, with Quintero allegedly touching her abusively and forcing her to consume cocaine while she was still under the influence of alcohol — in a state that, according to her testimony, prevented her from consenting or defending herself.

“I moved to Bogotá on June 29th, and for the first few weeks I was looking for a place to live, trying to settle in after a very intense move. One day, on July 25th, Julián and I went out to dinner. That same day, before we left to eat, he told me that he was no longer with Vannesa and that he was ‘acting like a crazy person.’ [Vanessa Morris was Quintero’s partner and one of the directors of Échele Cabeza.] He ordered wine. I prefer beer and don’t usually drink wine or liquor, but I thought it was a nice gesture for my first dinner with him. After two bottles of wine, I already felt drunk and told him that was enough, that I didn’t want any more wine. He said that was fine, that we could walk down the avenue, buy some beers, and then go to the Échele Cabeza house. That’s what we did.

While we were at the house, I remember him telling some people there — including one of his female friends and her friend — that I was a ‘gringa’ he had brought in to get resources for his projects. I was furious at what he was saying and at the way she was responding. At that moment, I was texting my partner about what was happening, but the messages didn’t make much sense, which showed how intoxicated I was. Julián probably kept offering me drinks; after that, I barely remember anything. I remember that all of this was happening in the living room of the Échele Cabeza house, an area with a security camera. Then I think I fell asleep and had memory gaps because I had drunk too much.

When I woke up, I was in another room, in a different part of the house. It was the room with the door directly across from the kitchen area where they do the psychological evaluations, and it’s soundproofed. When I woke up, he had his hand inside my bra and was touching me without my consent. He was also forcing me to take cocaine: I woke up feeling him shove it up my nose while I was still heavily sedated, and he was trying to kiss me”.

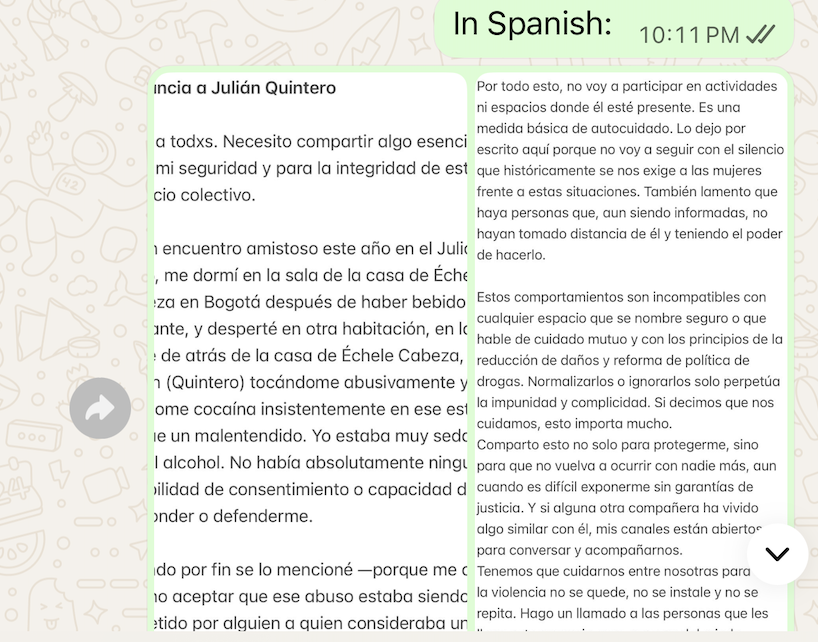

Yarelix assures that later, when she tried to talk about what had happened, Quintero’s response was to minimize what had happened. From then on, she decided to avoid places where he was present as a basic self-care measure. Estrada wrote her account of what had happened and shared it on internal networks and in messaging groups that include harm reduction organizations from different countries; she also filed a complaint with the appropriate authorities.

“From the time of the abuse until October, I felt that I was intentionally isolated from the Échele Cabeza project. In July, I asked the coordinator of the drug checking program, Mauro Díaz, if I could join as a volunteer, and he told me that they didn’t accept volunteers who had a partner within Échele Cabeza (because my partner is a volunteer in Medellín). That was a lie: there were several couples at Échele Cabeza, including Julián and Vannesa.

The only times Julián contacted me were to ask me to pressure my director into requesting $17,000 to buy an FTIR machine for drug checking for their project. In short, the only times Julián contacted me were when he needed or wanted something. It got to the point where I had to tell my boss to please let him know not to contact me anymore for resources or money, because I did not feel comfortable being used as a resource — as a commodity — both by someone who had abused me and by someone who was using me while I felt completely isolated in Bogotá. In October, I finally returned to New York City.

On the night of October 19, I sent Julián a voice note telling him that in Vienna it had not been right for him to take advantage of me when I was so drunk; that it had not been right for him to sexually assault me when I was unconscious on July 25 at the Échele Cabeza house; and that it had not been right for me to feel that he was using me for the resources of my organization and network all this time.

He replied that he was ‘very sorry,’ that he wanted to talk, and that he wanted to change things. He didn’t deny anything that had happened and told me that we should talk about it in Manizales, at the psychedelic conference where we were both going to present. The conference was on October 23rd and 24th”.

Detroit, November 12–15, 2025, International Drug Policy Reform Conference.

“I kept recounting what happened until I got to the International Drug Policy Reform Conference in Detroit. Julián was scheduled to speak there. One of the friends I told said he was going to be on a panel with me and suggested I tell the moderator and a member of the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) staff what he had done to me, because it was unfair that he was appearing at the conference. I contacted two DPA staff members. They eventually responded and told me they were removing him from the panel and disinviting him from the conference. For me, that was very important and helpful.

Almost no one doubted what I said, except for two of his best friends, who, from the moment I told them what happened, never stopped questioning me, making excuses for him, and doing damage control on his behalf — even during the conference. But many other people told me they believed me. They mentioned that they knew of other people who had come forward to denounce Julián’s abuses (sexual and emotional abuse, exploitation, theft of projects, and unequal labor relations), and that nothing ever happens because he has a monopoly on funding and power in harm reduction in Colombia.

During the conference, a lot of pressure began to mount in Bogotá because some of the workers within Acción Técnica Social (ATS) were trying to hold Julián accountable for what had happened. All the ATS leaders — except for Mauro Díaz, who defended Julián — were demanding that he be held responsible for his actions and that he leave the organization to prevent damage to the reputation of Échele Cabeza and ATS. At first, Julián acted as if he were sorry and pretended he was going to step aside, but the next day he told everyone that he already had a lawyer, that he felt they were harming him, and that he was considering taking legal action against the workers who were speaking out against him… and possibly against me as well. For me, it was completely unacceptable to let this go unpunished, so I drafted a short denunciation to share in WhatsApp groups about what had happened to me. From there, many people began to spread the word.

When I returned from the conference, I filed a formal complaint with the Prosecutor’s Office, recounting what had happened: when I was unconscious, Julián touched me inappropriately without my consent, gave me cocaine without my consent, and tried to kiss me. Since the news broke, at least four more women have contacted me to share their similar experiences. In each case, they were under the influence of alcohol, drugs, or both, and most of the incidents occurred inside what was then the Échele Cabeza house”.

Antonia

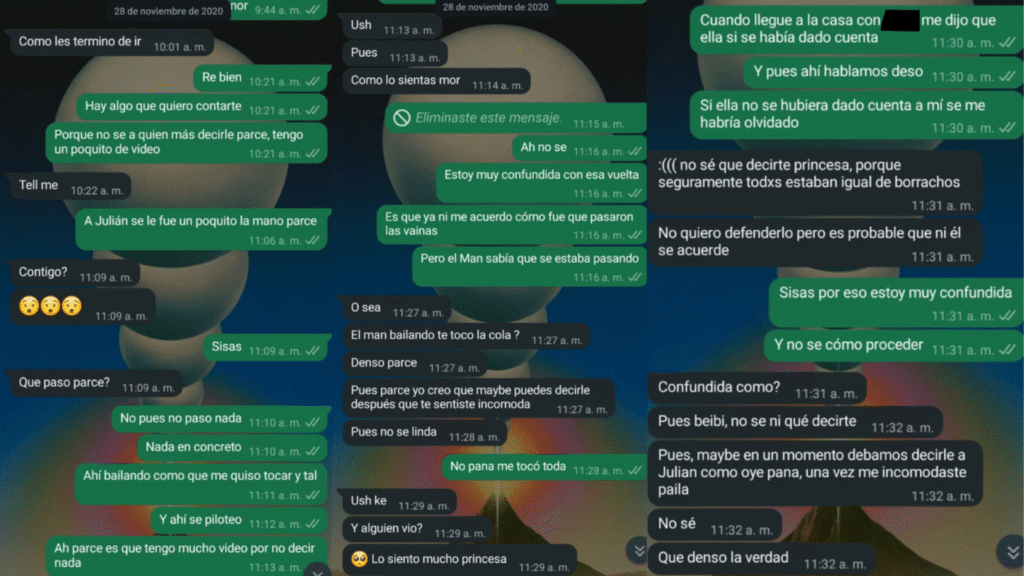

Antonia, a volunteer with Échele Cabeza since 2018, recounts that in November 2020, after a night of drinking at the organization’s headquarters, Quintero allegedly touched her private parts without her consent. She was 22 years old, and he was 42. Antonia filed a complaint with the Prosecutor’s Office regarding these events.

“I joined Échele Cabeza in 2018, through a recruitment call for women aimed at achieving gender balance within the organization. From the moment I joined, I developed a close relationship — even friendships — with other volunteers; however, I was never close to Julián. I saw him as the leader, someone I looked up to and admired for his role in harm reduction in the country. I always tried to maintain a good relationship with Julián and Vannesa, not only because they were the project leaders, but also because of the opportunities within the organization, such as attending large events, being considered for speaking engagements, or even participating in certificate programs abroad. For me, Échele Cabeza was an opportunity to work professionally on something I’m passionate about.

On November 27, 2020, I went to the Échele Cabeza house to celebrate a birthday. There were about 15 of us, and I was with someone I was dating at the time. From the beginning of the evening, I felt that Julián was very open to having a closer conversation with me; I was fine with it because it wasn’t something that usually happened in the spaces we shared with the whole group. We were all drinking and dancing. Julián and I were talking, and what I remember is that he grabbed my breast. I stepped back, confused, and he told me it was perfectly normal. He took my hand and placed it on his chest, making me squeeze it. I don’t know how I managed to avoid that strange conversation and move away from him. I think that at that moment it was very difficult to accept what was happening because for me that place was a safe space — not only because it was the Échele Cabeza house itself, but also because of the people I was with.

I continued talking with my friends and dancing when suddenly I felt someone press up behind me and pull me against his body. He grabbed my breasts and my vagina, and I realized it was Julián. I was stunned; it all happened so fast. I just stood there, frozen — I was so stunned I couldn’t speak. He reacted quickly, backing away and saying, ‘I can’t do this.’ But throughout the night, these unwanted sexual touches of my genitals happened three or four more times.

At one point, he told me, ‘If you feel I’m going too far, tell me.’ On one occasion, he tried to put his hand down my pants. That night is a blur for me, not only because of the alcohol, but because I didn’t understand what was happening, why it was happening, or why everything was happening so fast.

That night I stayed with the person I was seeing, and when I woke up, I felt very confused and vulnerable. This person mentioned that they had noticed what had happened and my discomfort at the party, and that they were worried. That same morning, I spoke with one of the volunteers from the organization who was very close to me and told her, in a superficial manner, what had happened and how I felt. In the following weeks, I also spoke with another volunteer who was close to me.

Looking back, I realize I downplayed everything that happened — and not just me, but also the people I told. They created an opportunity for Julián to apologize to me at Échele’s year-end party. What he said that night was more of a justification than an apology. He claimed it was because of the alcohol and because of ‘his age’; I never really understood what he meant by that.

I never felt comfortable in a space with him again, as he acted as if nothing had happened and as if we were just friends. At one point, I even had to find a private place to tell him I didn’t want him to touch me, since he used to hug me and make jokes like ruffling my hair. I told him I hoped we would keep our relationship strictly formal because, after what had happened, I didn’t feel comfortable with that kind of closeness.

There came a point when I no longer felt safe in volunteer settings. I stopped participating in many events and avoided any place where he was present. Even so, I held on to the idea that I could continue working in harm reduction and support the project from other perspectives besides volunteering at parties.

Today, I wonder why I stayed so long after what happened and the violence I was a victim of. I think that at that moment I felt the fear of being left out of Échele Cabeza, of not finding spaces where I could work on these issues, or even of suffering some retaliation for what had happened — which is what ended up happening.

I left the project — or rather, I was kicked out. In June 2022, I was notified that I was no longer part of the project, along with the other volunteers. We were asked to join a team meeting at the project’s old location without much explanation. On my way there, I noticed I had been removed from the WhatsApp group. When I arrived at the meeting, they cynically told us that things weren’t working within the group and that’s why they had decided to expel everyone from the volunteer program and hold a new recruitment call, which we could apply to if we wanted. I didn’t want to go back.

I consider it pertinent to mention that recently, after contacting Yarelix, I decided to file a complaint with the Prosecutor’s Office regarding the events of 2020″.

Cristina

One of the organization’s volunteers recounts that on February 15, 2024, also at the Échele Cabeza headquarters in Bogotá, after a night of heavy alcohol consumption and while very intoxicated, Quintero touched and kissed her without her consent.

“I was part of the Échele Cabeza volunteer group. On the day of the events, Vanessa Morris — Julián Quintero’s partner at the time — invited me to a meeting where he would also be present. First, we attended an event with other volunteers and then went to the Échele Cabeza house to continue the meeting. We consumed significant amounts of alcohol; I agreed to participate and ended up considerably intoxicated.

As the early hours of the morning approached, several people left, and only Vanessa, Julián, and I remained. My memories of that part of the night are fragmented. I recall noticing behavior from Julián that I interpreted as flirting, which made me uncomfortable — especially since his partner was present.

I’m not clear on how certain events began, but I do remember that I ended up kissing Julián. At some point, he took my hand and led me to another room; Vanessa was asleep on the sofa. I followed him largely because my level of intoxication limited my ability to assess or react clearly. In that room, he touched me and suggested I touch him; I shook my head. He stopped the interaction. I left, still dizzy and confused.

For a long time, I didn’t know how to interpret what had happened. I didn’t name it in any specific way because I was going through a very emotionally turbulent time myself, and I relied mainly on shame and guilt to try to understand it. I haven’t seen them since.

When I read Yarelix’s testimony, I cried. I don’t fully understand why I reacted that way or why I still cry when I remember it. Even now, I struggle to put a name to what I went through. The only thing I’m sure of is that I made decisions that put me in a vulnerable position, and that if I had been sober, I wouldn’t have agreed to what happened that night.

I share this because I believe it’s important that those who interact with these individuals in social or professional settings do so with sufficient information to set boundaries and make informed decisions, especially in contexts involving admiration, authority, or asymmetrical relationships. I aim to express my experience and the reflections that have emerged over time in the most responsible and honest way I can“.

Consumption without risk reduction

The three complainants agree that the Échele Cabeza headquarters in Bogotá is a frequent venue for parties where large quantities of alcohol and other substances are consumed. Regarding this, Yarelix states: “Part of the space they created felt safe, although at times it also felt dangerous. Julián and Vannesa fostered an environment that encouraged overconsumption — of alcohol, cocaine, and other stimulants — while simultaneously promising to protect anyone who decided to consume large amounts of different substances. I was one of the many women who chose the Échele Cabeza group and the Échele Cabeza house as a safe place to consume more than I normally would, or to consume substances I wouldn’t normally consume — like drinking a lot of alcohol and using cocaine, for example — because I believed I would be protected despite being in a vulnerable state“.

This complaint, now involving multiple women, touches on a particularly sensitive issue: sexual violence in spaces presented as safe and based on care. Estrada questions whether such abusive behavior is compatible with organizations that preach mutual care and work with at-risk populations.

This case brings to the forefront once again:

- The necessity for harm reduction to also include internal policies of care and consent, beyond the progressive rhetoric often adopted externally.

- The power imbalance between established figures in the field and younger collaborators, consultants, researchers, or volunteers.

- The urgent need for these spaces to have clear protocols for the prevention, reporting, and sanctioning of gender-based violence — protocols that do not depend solely on the reputation of their leaders.

Organizations such as Dejusticia, Elementa DDHH, Fundación Ideas para la Paz, Temblores NGO, Corporación Humanas, and CESED at the University of the Andes have expressed their solidarity with Estrada and the other women complainants, highlighting that harm reduction projects cannot be separated from commitments to human rights and gender justice.

Following the circulation of the complaint, ATS issued a public statement expressing its ‘zero tolerance’ for any form of gender-based violence, both within and outside the organization. In the statement, ATS:

- Supported Estrada’s decision to file a complaint and committed to ensuring an environment free from retaliation and revictimization.

- Announced that, effective immediately, Julián Quintero had been removed from his position as CEO of ATS and barred from any public or private representation on behalf of the corporation while internal procedures are underway.

- Committed to implementing measures for reparation and non-repetition.

However, this statement was removed from Échele Cabeza’s social media accounts. Quintero publicly denied having committed any physical, sexual, or psychological violence against Estrada and announced that he would initiate legal proceedings. Estrada has stated that she fears for her physical safety. “While “resigning,” he also said he wasn’t going to add anything more about the situation with me because that would “cause harm,” and I’m interpreting that as a threat to my safety“, she says. Antonia and Cristina’s intention not to reveal their identities reflects the fear that women in subordinate positions feel when making these kinds of accusations. Today, December 2nd, Échele Cabeza published a new statement confirming that Quintero was removed from the project and announcing that Vanessa will be assuming the project’s leadership.

According to the complainants’ lawyers, “the violence described above constitutes sexual violence against a person in a defenseless state, since, being highly intoxicated and under the influence of psychoactive substances, the complainants were not fully conscious of what was happening nor did they have the capacity to resist. This is clearly a common factor in each case. Julián Quintero was systematically aware of the women’s state of confusion and defenselessness, as well as his clear superiority, given his leadership role and high public profile in the harm reduction sector. Practices of intimidation and exclusion were used against some of the complainants, preventing them from participating in the Échele Cabeza and ATS collectives because they did not allow Julián Quintero to continue his abuse of power and sexual abuse. Having been harassed and touched without their consent, they were simultaneously excluded and marginalized from collective spaces. A power structure based on labor abuse, the usurpation of ideas and resources, as well as complicity in various forms of gender-based violence — such as sexual harassment, sexual abuse, psychological violence, economic violence, and property violence. Spaces of excessive consumption, where care was promised and large amounts of consumption were encouraged, were deliberately fostered and created as settings for sexual harassment and abuse. Each case demonstrates a systematic modus operandi of Julián Quintero and Vanessa Morris: Julián Quintero as the perpetrator of sexual violence, and Vanessa Morris as an accomplice through her silence, defense, and support“.

Yarelix and Antonia are demanding reparations. They demand:

- “That Julián Quintero and Vannesa Morris be removed from their positions due to the violence described here, as well as guarantees of non-repetition regarding their systematic actions.

- That, until real processes of reparation and comprehensive justice are carried out for each of the victims, Julián Quintero and Vannesa Morris be excluded from decision-making spaces, spokesperson roles, and leadership positions within the field of harm reduction and public health.

- The dissolution of Échele Cabeza and ATS as complicit and degraded structures that have enabled sexual harassment and abuse, labor exploitation, and the usurpation of women’s resources and ideas.

- The seizure of the Échele Cabeza house and its return to the SAE, given that it has repeatedly been a space where these forms of violence were carried out, making it unsafe for women.

- Security guarantees, given the ongoing fear for our integrity and our lives due to the power these two individuals exercise within the harm reduction field in Colombia”.

__________________________________________________________________________

Volcánicas sent some questions related to these allegations to Julián Quintero and Vanessa Morris. Quintero responded that he could not give interviews at the moment, and Morris also told us that she would not be responding to interview requests due to matters involving her lawyers. However, we are sharing the questions we sent to both of them:

Questions for Julián Quintero

- Did you meet Yarelix Estrada in Vienna in March 2025?

- Did you remove Yarelix Estrada’s clothes and touch her on the night of March 12, 2025, while she was visibly intoxicated?

- Did you ask for and receive Yarelix Estrada’s consent to undress and touch her that night?

- Did you meet Yarelix Estrada in Bogotá in July 2025?

- On the night of July 25, 2025, at the Échele Cabeza headquarters, did you touch Yarelix Estrada’s breasts under her shirt while she was visibly intoxicated?

- Did you ask for and receive Yarelix Estrada’s consent to touch her that night?

- On the night of July 25, 2025, at the Échele Cabeza headquarters, did you attempt to give cocaine to Yarelix Estrada when she was visibly intoxicated and unable to give consent?

- On the night of February 15, 2024, were you consuming alcohol at the Échele Cabeza headquarters in Bogotá with volunteers and other members of the organization, including your partner at that time, Vannesa Morris?

- That night, did you kiss one of the volunteers, who was visibly intoxicated?

- Did you consume alcohol on November 27, 2020, at the Échele Cabeza headquarters in Bogotá with volunteers and other members of the organization?

- Did you touch the breasts and other intimate parts of one of the volunteers that night?

- Did you ask for and receive the volunteer’s consent for that touching?

- What is your current connection with the Échele Cabeza organization and with ATS?

Questions for Vanessa Morris

- On the night of February 15, 2024, were you consuming alcohol at the Échele Cabeza headquarters in Bogotá with volunteers and other members of the organization, including your partner at the time, Julián Quintero?

- That night, did you see Julián Quintero kissing one of the volunteers, who was visibly intoxicated?

- Have you witnessed or had direct knowledge of Julián Quintero making sexual advances toward women who have volunteered or worked at Échele Cabeza?

Por

Por